Downloads

Fake music. Records designed to deceive unwitting customers into believing there's more there than there really is. Sleazy record companies have been contriving ways to fool frugal buyers since the dawn of recorded music. The methods these con artists use are often so clever and amusing that it can be hard to stay mad at them.

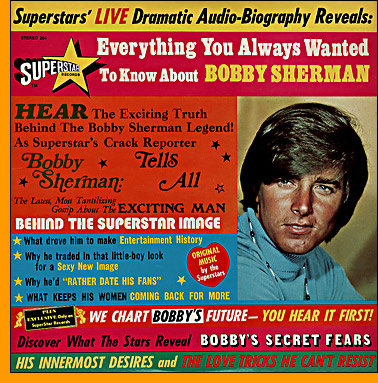

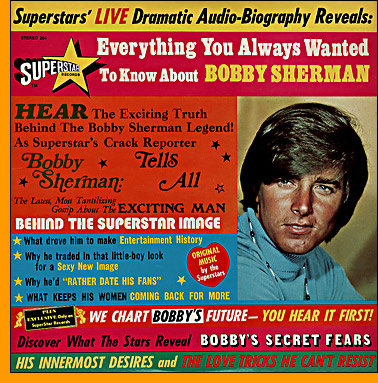

High in the annals of great fake music ranks a series of albums on the Superstar label, out of Broadway, Times Square, New York, New York. The brainstorm of a slick operator known as Ernie T., Superstar Records put out four albums in the early '70s that appeared, when viewed at a glance, to be new releases by the hottest teenypop idols of the day: The Osmond Brothers, Bobby Sherman, David Cassidy, and the dark horse entry, The [sic] Grand Funk Railroad. In the spirit of trendy reference, the series was called Everything You Always Wanted To Know About ..., each title concluding with the name of the respective artist. The cover would feature a photo of the title idol dropped haphazardly amidst a barrage of screaming, multifonted headlines -- "The Girls That Excite Them! The Girls That Turn Them Off!" -- the type jumbled inside a random array of circles, boxes, hearts and stars. Were it not for the squared size, Superstar's cover art could easily be mistaken for Tiger Beat or 16 magazines, or perhaps even a carton of Lucky Charms.

One of Ernie T.'s most brilliant strokes was the name he assigned to the performer of the actual musical content: "Original Music by The Superstars," read a red heart on each cover. Surely the kiddies were too hip to ever fall for this ruse, but what bargain-hunting mom could be expected to stop and think about that phrasing for a moment, to not subconsciously extrapolate Ernie's ingenious trick of the language until it became, in her mind: " Original Music by The Osmonds Brothers," or "Original Music by David Cassidy"? But rather than any genuine hitmakers, The Superstars were an anonymous studio group flung together to record the lukewarm generic rock that underscores the series' hyperbolic "Audio-Biographies."

To summarize, little Lorna would be given a copy of Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Bobby Sherman for her thirteenth birthday, put it on expecting to bop to "Hey, Little Woman" or "Julie, Do Ya Love Me," but hear instead a dizzy-sounding young woman chattering incessantly about Bobby's upbringing, his love life and secret yearnings while a continual stream of sludgy, decidedly non-Shermanesque rock rumbles underfoot. How could she fail to be crestfallen or, if she were old enough, pissed off? But, too late, no refunds ... next sucker, please!

Ernie T. got off on that. "He loved that it was legal, but such a put-on," Superstar scriptwriter Joe Kane remembers. "He loved the idea of white teenyboppers buying this album." Ernest L. Tucker was the brains behind the Superstar label, a black P.T. Barnum for the '70s. Ernie T. was a capitalist and a racist, who hated whites and delighted in outsmarting them. He walked around with a briefcase full of cash, dispensing from it only when absolutely necessary. "He was a very funny guy," recalls the engineer who cut most of Ernie's recordings. "He had a lot of personality. You know The Jeffersons? He reminded me of that guy, only with the pimp hat." If he didn't quite resemble George Jefferson, then perhaps he looked like another black superstar. "He reminded me a little of a postmodern Sammy Davis," says Joe Kane. "He was not too big and very slim. Thin tie, mustache -- that kind of hip idea. He wore a dollar sign tie-pin, and he was proud of it. He was a parody. He was very smart, and very aware of what he was doing. He appreciated very much the scam, or legal scam, he was putting on."

Ernie T. had laid out for himself a little empire of sleaze there in Times Square, where it could hardly be noticed. The fact that he conceived the Superstar scam as his attempt to go legit puts the rest of his career into perspective. At least one of his former employees believes his real occupation was as a pimp; those others who hadn't heard that agreed that, at the very least, it suited his style. Ernie and his main lady, Miss B. Fannie, a white, blonde Southern chick, marketed under her name a line of marital aids. "I went one time to his factory," recalls the engineer. "It was a place on 7th Avenue, a big room where he had a bunch of old women stuffing records and French ticklers. He was selling these things for ten, eleven dollars." Both the ticklers and the records were sold by mail order.

Miss B. Fannie's French ticklers were advertised regularly in Screw, Al Goldstein's weekly sex rag. Through Goldstein Ernie was introduced to Joe Kane, the writer of Screw's popular "Smut From The Past" column, and hired him to come up with the text for a Rolling Stones album -- not by The Stones, of course, but about them. Although Kane completed a script for it, the Stones' volume was never released. Kane then introduced Ernie to some of his friends. Maria Zannieri, a writer and editor for Dell Publications' line of movie gossip magazines, took care of David Cassidy; Jerry Kantor, a graduate student in philosophy at City University of New York, was assigned to tackle Grand Funk Railroad; and Marie Morreale, Zannieri's assistant at Dell, was given the gift of Bobby Sherman. (The script for the Osmond Brothers album is credited to Noel Hamilton, a person nobody contacted for this story recalls.)

The writers were paid by the word, a fact that goes a long way toward explaining the peculiarly breakneck style of the patter. The more words the writers wrote, the more money they made, but the time available to get in all those words was limited. "Ernie felt very strongly about not being cheated," Zannieri told me. "I really do believe he probably didn't know how to read, but he knew how to count. You'd deliver a script and he would say things like, 'Wow, this script is a little light, don't you think?' And he would comment on how wide the margins were. He didn't seem to have a concept of good writing or bad writing, but he sure did know if you had used a lot of words." This doesn't make sense, of course -- the more words that were used, the more Ernie would have to pay the writers, so isn't he cheating himself by demanding "heavier" copy? But Ernie T. works in mysterious ways.

The scripts fetched about $200 for their authors, who needed only to stitch the texts together from squiggly articles clipped from pre-teen fan mags. Given the fact that their subjects were people who had hardly yet begun to live, it was no mean trick getting anything meaty on the page. "When I wrote the script about David Cassidy, he was, what, 24 or something?," Zannieri asks rhetorically. "So what was there to say? I think I said a lot about his terrible case of the measles." Indeed, she referred to his gall bladder surgery in the third sentence of her script. Most of the second side of Morreale's Bobby Sherman script is given over to a discussion of his horoscope reading -- "We Chart Bobby's Future -- You Hear It First!"

The scripts fetched about $200 for their authors, who needed only to stitch the texts together from squiggly articles clipped from pre-teen fan mags. Given the fact that their subjects were people who had hardly yet begun to live, it was no mean trick getting anything meaty on the page. "When I wrote the script about David Cassidy, he was, what, 24 or something?," Zannieri asks rhetorically. "So what was there to say? I think I said a lot about his terrible case of the measles." Indeed, she referred to his gall bladder surgery in the third sentence of her script. Most of the second side of Morreale's Bobby Sherman script is given over to a discussion of his horoscope reading -- "We Chart Bobby's Future -- You Hear It First!"

Even though they were eager kids trying their best to do a good job, the writers surely could have stood the hand of a good editor. Run-on sentences dart snakily all over the copy. Humorous mistakes -- George Hamilton's "My Sweet Lord," Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tom Rice, the Muddy Rivers Blues Band -- are left to fend for themselves. But Ernie T.'s inattentiveness to the content was ultimately a boon, leaving the staff free to play things fast and loose. "The writing was totally tongue-in-cheek," says Zannieri. "It was kind of a game for us, when we were writing house copy for the fan magazines, to see how much we could get away with." That approach carried over to the Superstar series. Inane though the copy was, it was also deceptively intelligent, at times even mildly subversive. Zannieri introduces Shirley Jones by calling her "apple-cheeked, clear-eyed and full-breasted." Kantor writes that Terry Knight, Grand Funk's Svengali, "is one hard cat to forget, once he gets stamped on that photoplate in the back of your mind." He goes on to spend long minutes explaining what a jerk Knight was: "Knight has an ego whose capacity for expansion might only be compared to the gases found in the hemispheres of other planets." Zannieri broadly hints that Susan Dey, whom the teenmags were portraying as the chief rival to everygirl's chances at snaring David Cassidy for herself, might be a lesbian: "Susan is grateful for the companionship of Jane, the young woman who shares her apartment. They feel they share a very special bond. ... In interviews, Susan avoids mentioning any special guy. As a matter of fact, she doesn't seem particularly interested in men."

The writers were offered another $50 to narrate their own copy, but only the two women -- Zannieri and Morreale -- accepted. The other readers, or "Superstars Aural Reporters," in Ernie T.'s curious parlance, were young actors. Rebecca Maiden, a Southern chick herself, aurally reported on The Osmonds, while Justin Franklin, the only male voice heard on the Superstar label, reads the Grand Funk text. He sounds like a cross between the announcer on the "Sunday! Sunday! Sunday!" speedway commercials and Eb from Green Acres. Each of the four seems to have been schooled at the same drama academy. They read their copy in a similarly loopy style, their breathless deliveries sounding like those of a kid who was chased out of a farm town for being too smart.

Likewise, the scenarios of the four albums unfurl in Identikit fashion. Crudely looped tapes of screaming-teen crowd noises (with the seam clearly audible) start off each album, the music fades in for a few bars, the crowd sounds fade out, and finally we hear the voice of the Superstars Aural Reporter. The narrators are so fresh and sprightly, their voices so full of pep and good cheer and mixed so loudly against the music of The Superstars, that their entry comes as a bracing slap to the face, the kind you're supposed to say "Thanks, I needed that" after receiving.

Matching the delivery, the words are also fresh and loopy:

Is this what makes The Osmonds so appealing in a rockrageous world?

What makes Bobby Sherman a superstar? Is it superior talent? Or is it those turn-on blue eyes and incredible good looks?

It's as obvious as the mustache on Frank Zappa's face that the tenor of Grand Funk's triumphs has not appreciably affected the modest, down-to-earth quality of the boys' lives.

Shirley Jones was right when she described David as a very private person, a person who feels as if he is copping out on his friends. But Shirley was describing the old David Cassidy -- the new David Cassidy is copping out no longer!

As media gadfly David Greenberger once noted, "Words spoken out loud take on different qualities and powers when committed to the page." Conversely, words that come across as peurile on the pages of teen idol magazines can sound positively uplifting when read aloud by a chirpy, eager young Aural Reporter, especially if she or he has the music of The Superstars along for support. The Superstars are a unique outfit, whose work on all four of these albums consists of fade-in/fade-out extracts of long, aimless jam sessions. Apparently, the band was told to just crank up and play whatever they felt like for 20 minutes or more. They would work out the basic changes of each piece in advance, then proceed to riff on them for the duration. When one piece had gone on long enough, they would end it, break for a smoke, then start in on the next. With this raw material at hand, the mixdown engineer could run a "song" seamlessly under an entire side of text.

We rarely get to hear an actual beginning or ending of a piece. The one exception is on the Bobby Sherman album, where a few of the pieces are brought to stumbling conclusions. But the narrator keeps right on reading (the words and music were always recorded separately, and only brought together at the mixdown stage), and there's a jarring, musicless gap before the next piece begins.

All four albums are clearly recorded by the same quartet of keyboards, guitar, bass and drums. To this day no one, save perhaps Ernie T., knows the names of the musicians behind those instruments, but it's doubtful that any of them have gone on to become famous. Their abilities can be quantified in descending order of technical skill. Best of the lot is the guitarist, who wavers between clear and sinewy but uninspired leads and tight, slightly fuzzed rhythmic comping. The keyboard player isn't a terrible musician, either. His style is to vacillate, without apparent provocation, between honky-tonk piano and tepid organ swirls in the manner of Alan Price or Georgie Fame. The bass player is negligible, as he is invariably locked into the guitarist's chords, never budging from their basic structure. His sound is mushy, ballsless.

Both worst and best is the drummer, who is the band's least talented and yet most exciting musician. His anxious struggles to keep steady time, arbitrarily punctuated by wreckless cymbal bashing, keeps the listener at the edge of his seat, with breath held and fingers crossed in hope of not falling off. Together, The Superstars sound not unlike some of Mike Curb's generic soundtrack stuff on Tower, the genre appropriation albums on Los Angeles' Crown label, or a "Hard Rock" selection from a needledrop library. On its own it's only OK, but in context it's pretty darn cool.

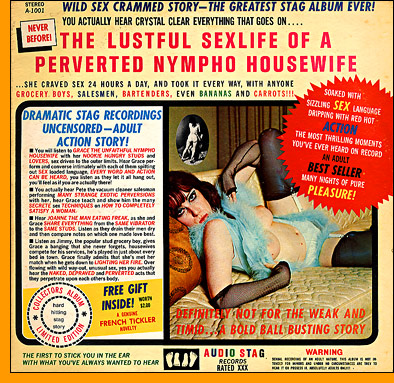

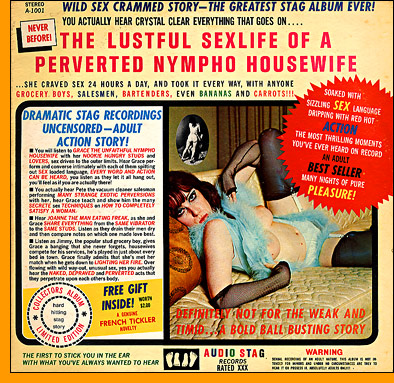

Superstar was not Ernie T.'s only ripoff record company. Perhaps more well-known is Audio Stag, Superstar's smutty cousin. Audio Stag featured aggressively bad actors attacking hysterical vignettes that, like a hardcore porn film, disintegrate quickly into outright fucky-sucky. The flimsy storylines run similar to those of stag flicks, including several that were based on some piece of then-popular culture. Watergate, All In The Family and Shaft come in for parody treatment; the delivery boy-turned-stud is a stock scenario, as is the lonely housewife, the best-friend couples hot for each others' spouse ... you get the picture.

Superstar was not Ernie T.'s only ripoff record company. Perhaps more well-known is Audio Stag, Superstar's smutty cousin. Audio Stag featured aggressively bad actors attacking hysterical vignettes that, like a hardcore porn film, disintegrate quickly into outright fucky-sucky. The flimsy storylines run similar to those of stag flicks, including several that were based on some piece of then-popular culture. Watergate, All In The Family and Shaft come in for parody treatment; the delivery boy-turned-stud is a stock scenario, as is the lonely housewife, the best-friend couples hot for each others' spouse ... you get the picture.

Unlike adult films, which are usually semi-improvised, the Audio Stag sessions were played strictly by the book. "The actors would come in and sit on a stool and read the script," recalls the engineer. The tapings "were kind of serious, in a way. I don't remember anybody laughing about it. They just did the job." Without any visuals (apart from the dizzying album jackets, immediately identifiable as having been designed by the same hand as the Superstar series), spoken words and sound effects were the only tools the Audio Stag players had at hand to create their hilariously vile little mind pictures, and so those words had to be even filthier than in the average porno flick. Or, at least, even more ludicrous:

Baby, I would swim through a pool of shit and vomit to get some pussy!

This is the best fucking blowjob I've ever had. Oh, oh ... kid, your tongue is saying "cockadoodledandy" on my dick! Ho-ho ... aw, suck it bitch, suck it!

I wish my wife could see me coming. Oh, I wish my secretary could see me coming. Ah, fuck ... I wish the whole goddamn shitty world could see me coming! Open your mouth, bitch, 'cause here I come!

You bitch! You must be reading my cunt-sucking mind!

Replacing the music of The Superstars is a complement of absurd sound effects. Bedsprings, beds moving across the floor, slapping flesh, gagging, moaning -- eight crude simulations of the sounds of raw Doin' It were prerecorded, with each assigned to one track of an eight-track tape. According to the engineer, "we made the sounds using chairs, springs, sponges, things like that. We put 'em on an eight-track loop and faded 'em in according to dialogue. Rattling chair sounds, palm-smacking sounds. It was funny at the time. The loop was just continuously running. As soon as we'd get to an action section, we'd add and increase the sound effects, ride the faders up, build up some kind of a frenzy." As in some of the stories they were aurally illustrating, "the hard part was pulling them out. If you listen carefully you'll see that the act is over and the noise is still there sometimes. Very low-budget." Sometimes a female groan loop would still be running after the actress had resumed speaking, thus inadvertently turning a one-on-one session into a temporary three-way.

Audio Stag albums came with a coupon insert which could be mailed in in exchange for one of Miss B. Fannie's French ticklers. The 8-track cartridges came with the ticklers attached. I even seem to recall seeing one of their 8-tracks with the tickler stretched across the cartridge, acting as both shrink-wrap and souvenir birth control device, but I might have fantasized that one.

It's hard to tell just how many albums Audio Stag put out, as Ernie T. released the same set of albums on at least three different occasions, sometimes with the same titles, sometimes changing the names midstream. Until a copy of each record comes to our attention and can be compared to the others, we can only guess which albums in one set match up to those in another. See the Audio Stag discography page, which includes some interesting surprises.

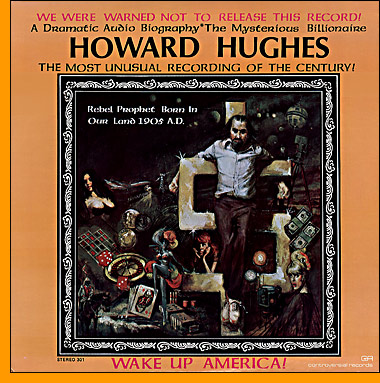

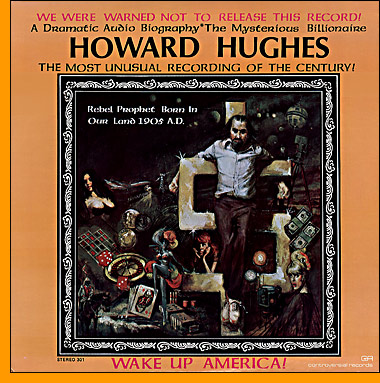

Ernie T. saved his most bizarre and masterful recorded accomplishment for a standalone release, 1972's Dramatic Audio Biography Of The Mysterious Billionaire Howard Hughes (aka Howard Hughes, The Prophet), on Controversial Records. Swaddled in enough echo to fracture middle Earth, interjected by sound effects both outlandish (such as cracks of thunder and screeching wind to illustrate the birth of the baby Hughes) and campishly obvious, the stentorian tones of "Drama, Vocal Performer" John McKay confer Richard Davidson's over-the-top script with an air of mega-importance. Davidson's persistent comparisons between Hughes and Jesus do little to soften the tone: "He's the man stretched out on a cross of gold. Like the Jesus of old he is a man who goes his own way. Like the Son of God, he too is a rebel and a thorn in the side of authority. ... You might ask yourself, How can we compare Hughes to a prophet like Christ? Because in his earlier years Hughes enjoyed the company of so many beautiful women. Well, did not Christ mingle with all the people? So Hughes mingled with all the people."

And what was it that this prophet Hughes foresaw with his mighty prophesying powers? Breasts. Although not just any breasts, mind you: "He spent a great deal of time [as director of The Outlaw] concentrating on Jane Russell's breasts. Scene after scene was centered on her special equipment. ... There on the spot he designed a new cantilever brassiere for her, one that without straps would give her breasts the proper rise and fall, as she squirmed in cinema agony. ... He took sex out of the drawing room and brought it into full view!"

And what was it that this prophet Hughes foresaw with his mighty prophesying powers? Breasts. Although not just any breasts, mind you: "He spent a great deal of time [as director of The Outlaw] concentrating on Jane Russell's breasts. Scene after scene was centered on her special equipment. ... There on the spot he designed a new cantilever brassiere for her, one that without straps would give her breasts the proper rise and fall, as she squirmed in cinema agony. ... He took sex out of the drawing room and brought it into full view!"

Howard Hughes, The Prophet is riddled with hilarious bits, all rendered that much more ridiculous by McKay's snarling delivery:

As a boy, Hughes loved music, and taught himself to play the saxophone. Hughes loved the underground music of his time. Hughes played what some today would consider the hard rock of his time.

He is a prophet who has loved many aeroplanes, and made love to many women.

Now today we have our hippies, our dropouts. Isn't Hughes, then, a kind of giant hippie, the man with the sneakers and the long hair -- unshaven, unkempt, but still regal, and beyond that word "regal" to "prophet"?

Howard Hughes -- Super Billionaire, Super Rebel, Super Prophet and Superstar!

Ernie T.'s staffers believe that with the Hughes masterstroke, his career as record producer reached its zenith and there was nothing more for him to accomplish in that arena. Another series of Superstar Audio-Biographies, to include The Jackson Five and most likely Kane's aborted Rolling Stones album, was planned but never completed. And with that the operation quietly came to a close.

A few years later, a rather plausible rumor about Ernie T. reached one of the Superstar writers. "I heard that he had gotten busted for another scam, where he sold something like How To Make $10,000 In A Week through a magazine ad. You'd pay whatever it was, $10 or $20, and what you'd get is a kit which told you how to place the same ad. I think he thought it was legal, 'cause he was doing it at the time I knew him."

The story has an appropriate upshot: "The last time I heard his name -- I don't know if this was connected to that same case of fraud -- but he conned the NAACP into defending him. I'm listening on radio and I hear on the news, 'This is an example of African-Americans getting prejudicial treatment by the courts,' and the name was Ernest Tucker. And I said, "Oh man, he's great, he can con them too." I think what he prided himself on was that he was all but holding up a sign saying 'I'm ripping you off, come and get it anyway. And if you're dumb enough, you deserve it.' That's how he thought."

Special thanks to Tom Ardolino, Jeff Conolly, Joe Kane, Jerry Kantor, Reed Lappin, Mike Stax, Gregg Turkington, Wayno and Maria Zannieri.

This article previously appeared in issue #18 of Ugly Things magazine.

| Where are they now || Ernie T. discography || Downloads |

The scripts fetched about $200 for their authors, who needed only to stitch the texts together from squiggly articles clipped from pre-teen fan mags. Given the fact that their subjects were people who had hardly yet begun to live, it was no mean trick getting anything meaty on the page. "When I wrote the script about David Cassidy, he was, what, 24 or something?," Zannieri asks rhetorically. "So what was there to say? I think I said a lot about his terrible case of the measles." Indeed, she referred to his gall bladder surgery in the third sentence of her script. Most of the second side of Morreale's Bobby Sherman script is given over to a discussion of his horoscope reading -- "We Chart Bobby's Future -- You Hear It First!"

The scripts fetched about $200 for their authors, who needed only to stitch the texts together from squiggly articles clipped from pre-teen fan mags. Given the fact that their subjects were people who had hardly yet begun to live, it was no mean trick getting anything meaty on the page. "When I wrote the script about David Cassidy, he was, what, 24 or something?," Zannieri asks rhetorically. "So what was there to say? I think I said a lot about his terrible case of the measles." Indeed, she referred to his gall bladder surgery in the third sentence of her script. Most of the second side of Morreale's Bobby Sherman script is given over to a discussion of his horoscope reading -- "We Chart Bobby's Future -- You Hear It First!"

Superstar was not Ernie T.'s only ripoff record company. Perhaps more well-known is Audio Stag, Superstar's smutty cousin. Audio Stag featured aggressively bad actors attacking hysterical vignettes that, like a hardcore porn film, disintegrate quickly into outright fucky-sucky. The flimsy storylines run similar to those of stag flicks, including several that were based on some piece of then-popular culture. Watergate, All In The Family and Shaft come in for parody treatment; the delivery boy-turned-stud is a stock scenario, as is the lonely housewife, the best-friend couples hot for each others' spouse ... you get the picture.

Superstar was not Ernie T.'s only ripoff record company. Perhaps more well-known is Audio Stag, Superstar's smutty cousin. Audio Stag featured aggressively bad actors attacking hysterical vignettes that, like a hardcore porn film, disintegrate quickly into outright fucky-sucky. The flimsy storylines run similar to those of stag flicks, including several that were based on some piece of then-popular culture. Watergate, All In The Family and Shaft come in for parody treatment; the delivery boy-turned-stud is a stock scenario, as is the lonely housewife, the best-friend couples hot for each others' spouse ... you get the picture. And what was it that this prophet Hughes foresaw with his mighty prophesying powers? Breasts. Although not just any breasts, mind you: "He spent a great deal of time [as director of The Outlaw] concentrating on Jane Russell's breasts. Scene after scene was centered on her special equipment. ... There on the spot he designed a new cantilever brassiere for her, one that without straps would give her breasts the proper rise and fall, as she squirmed in cinema agony. ... He took sex out of the drawing room and brought it into full view!"

And what was it that this prophet Hughes foresaw with his mighty prophesying powers? Breasts. Although not just any breasts, mind you: "He spent a great deal of time [as director of The Outlaw] concentrating on Jane Russell's breasts. Scene after scene was centered on her special equipment. ... There on the spot he designed a new cantilever brassiere for her, one that without straps would give her breasts the proper rise and fall, as she squirmed in cinema agony. ... He took sex out of the drawing room and brought it into full view!"